Patient safety is the heart of every operation in the operating room. Although cardiac arrest in an operating room is rare, it is a serious event, often triggered by respiratory problems, severe allergic reactions, or heart-related issues such as blood loss, embolisms, or acute coronary syndrome. When it occurs during surgery, it brings unique challenges. The environment is complex, equipment surrounds the patient, and quick decisions matter more than ever. This article will explore how CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) works in a surgical setting, why it differs from other situations, and how medical teams act fast to protect lives when every second counts.

Understanding Cardiac Arrest in the OT

Cardiac arrest in the operating room is rare but serious, and knowing why it happens can save lives. Understanding the causes, risks, and how the body reacts under anesthesia helps the team act quickly and confidently.

1. Common Causes of Intraoperative Cardiac Arrest (ICA)

Cardiac arrest during surgery is uncommon but often results from identifiable and sometimes preventable factors. The most frequent causes include:

- Anesthetic Complications: Overdose of anesthetic agents, airway obstruction, or severe allergic reactions (e.g., anaphylaxis) can depress cardiovascular function.

- Severe Hemorrhage: Massive blood loss reduces circulating volume and oxygen delivery, leading to hypovolemic cardiac arrest.

- Electrolyte Imbalances: Abnormal potassium, calcium, or magnesium levels can trigger lethal arrhythmias.

- Arrhythmias: Ventricular fibrillation, asystole, or pulseless electrical activity may occur due to drug effects, hypoxia, or underlying heart disease.

- Surgical Causes: Manipulation of the heart or major vessels, embolism (air, fat, or thrombus), or tension pneumothorax during thoracic or laparoscopic procedures.

Early identification and prompt correction of these triggers are essential to prevent full cardiac arrest.

2. Incidence and Risk Factors Specific to Surgical Patients

Intraoperative cardiac arrest (ICA) is rare, occurring in approximately 1 to 20 per 10,000 anesthetics, depending on patient health and procedure type.

Risk is higher in:

- Emergency surgeries where preoperative optimization is limited.

- Elderly patients or those with existing cardiac, respiratory, or renal disease.

- High-risk surgeries such as cardiac, neurosurgical, or major trauma operations.

- Prolonged surgeries with significant fluid shifts or blood loss.

- ASA physical status IV–V patients, who already have severe systemic disease.

Understanding these risk profiles assists the perioperative team in anticipating and preparing for potential cardiac events.

3. Physiological Differences Under Anesthesia

Resuscitation in anesthetized patients differs significantly from that in awake individuals due to altered physiology:

- Depressed Autonomic Responses: Anesthesia blunts sympathetic drive, making hypotension and bradycardia less noticeable until severe.

- Reduced Oxygen Reserve: Muscle relaxation and mechanical ventilation affect normal respiratory physiology, leading to rapid desaturation.

- Altered Cardiovascular Tone: Anesthetic agents can cause vasodilation and myocardial depression, complicating resuscitation.

- Limited Clinical Signs: Patients are draped, immobile, and fully monitored, so cardiac arrest is recognized through equipment readings (loss of end-tidal CO₂, flat arterial trace) rather than visible symptoms.

How Intraoperative CPR Differs from Standard CPR

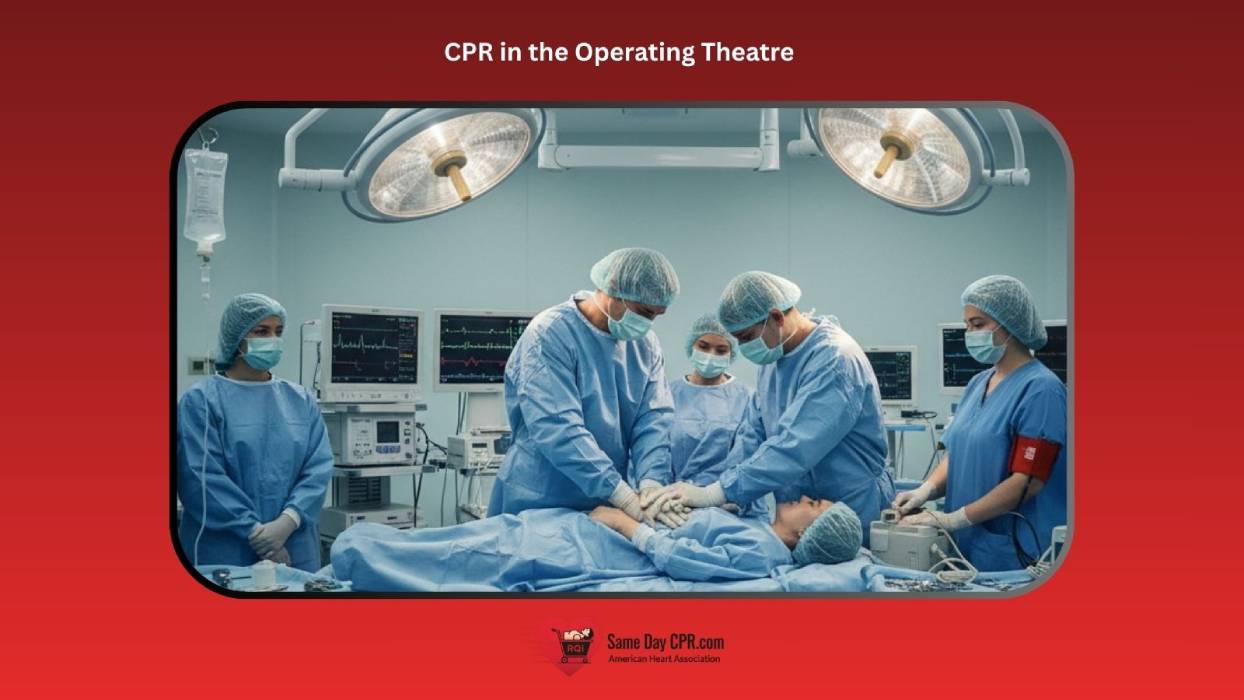

Intraoperative CPR is not the same as standard CPR because it involves different triggers, faster response times, and access to specialized equipment, which can improve survival chances. Unlike CPR outside the operating room, it is carried out by skilled surgical and anesthesia teams in a controlled setting.

1. Intraoperative CPR

Intraoperative CPR happens during surgery when a patient’s heart stops, and the medical team must act right away to keep blood flowing.

- Context: It takes place in the operating room where the patient is under anesthesia and closely monitored by the surgical and anesthesia team.

- Technique: Chest compressions are done carefully to avoid harming surgical sites, sometimes using open-chest methods for better results.

- Goal: The main aim is to quickly restore blood flow and oxygen to vital organs while keeping surgical control and patient safety in mind.

- Rescuer: The anesthesia and surgical team work together closely, each focusing on their specific roles to give the best possible care during the emergency.

2. Standard CPR

Standard CPR performed outside the operating room when someone’s heart suddenly stops, and immediate action is needed to save their life.

- Context: It usually happens in public places, homes, or hospitals without surgical procedures involved.

- Technique: The rescuer gives chest compressions and rescue breaths in cycles to keep oxygen and blood moving through the body.

- Goal: The main goal is to restart the heart and maintain oxygen delivery to the brain and vital organs until help arrives.

- Rescuer: It can be done by anyone trained in CPR, from bystanders and first responders to healthcare professionals.

Immediate Response and Crisis Management Protocols

In the operating room, quick recognition of cardiac arrest is vital because every second matters. The team constantly watches the patient’s vital signs, ECG (electrocardiogram), and capnography to spot sudden changes that might signal the heart has stopped. Once cardiac arrest is suspected, the team immediately activates a code blue or emergency response to bring in extra help and equipment. The response is highly organized, with each person knowing exactly what to do. The anesthesiologist manages the airway, breathing, and medications, while the surgeons handle the surgical field and control bleeding if needed. Nurses prepare emergency drugs, assist with compressions, and ensure everything runs smoothly. Support staff help with equipment and communication, allowing the whole team to work together efficiently and giving the patient the best possible chance of recovery.

Step-by-Step Approach to Effective OT CPR

This guide lays out a clear sequence that the operating room staff can follow to act quickly and stay organized when a patient has cardiac arrest. Work through it to protect the airway, support circulation, keep the surgical field safe, and restore blood flow.

Step 1: Immediate Recognition

If someone suddenly collapses or stops breathing, check right away. Look for unresponsiveness, no normal breathing, or no movement. These quick checks help you decide what’s happening so you can act fast and stay calm.

Step 2: Call for Help

If the person doesn’t respond, shout for help and call emergency services immediately. If you’re alone, use your phone on speaker so you can start helping while waiting for responders. Getting trained help as soon as possible can save a life.

Step 3: Ensure Airway and Ventilation

Gently tilt the head back and lift the chin to open the airway. Check for normal breathing, look, listen, and feel. If they’re not breathing normally, begin rescue breaths if you know how. Clear the mouth only if you see something blocking it, and keep breathing steadily and gently.

Step 4: Chest Compressions

Place your hands in the center of the chest and push hard and fast, about 100 to 120 times per minute (roughly two per second). Let the chest rise fully between pushes. Keep going until help arrives or the person starts to move or breathe.

Step 5: Defibrillation

If there’s an AED (automated external defibrillator) nearby, turn it on and follow the prompts. Attach the pads as shown on the diagrams. Make sure to review when you should clear the victim while operating the AED so you know exactly when to stand clear. Don’t touch the person while the device analyzes. If it says a shock is needed, deliver it and resume CPR immediately as directed.

Step 6: Address Reversible Causes

Think about possible causes, such as heart problems, breathing issues, or injuries. If you can safely correct something reversible, do it while waiting for help. Stay focused, communicate clearly, and follow what you’ve learned.

Also, Read: Reversible Causes of Cardiac Arrest H’s and T’s

Post-Resuscitation Management in the OT

After a patient regains a pulse in the operating room, the focus shifts to keeping them stable and preventing complications. The team quickly checks vital signs, supports breathing, and ensures the heart is working properly. Oxygen levels, blood pressure, and temperature are closely watched while any underlying issues are treated right away. It’s important to look out for rhythm changes, low oxygen, or low blood pressure that could cause another arrest. Once the patient is stable, every step and observation is clearly recorded, and the team takes time to talk through what happened. This helps everyone learn, improve their response, and provide even better care next time.

Team Coordination: The Heart of Successful Intraoperative CPR

Team coordination is the heartbeat of successful intraoperative CPR. When a patient’s heart stops during surgery, every team member must know their role and act fast. The anesthesiologist manages the airway and medications, while the surgeon focuses on internal factors that might have caused the arrest. Nurses and techs work together to bring in needed equipment and keep the environment calm. Clear communication keeps everyone focused and prevents confusion. When the team moves with unity and trust, their combined efforts give the patient the best possible chance for recovery.

Protecting Life in the Operating Theatre (OT)

In the operating room, every heartbeat matters, and teamwork truly saves lives. When cardiac arrest happens during surgery, it demands calm minds, skilled hands, and instant action. Each team member knows their role, whether it’s managing the airway, controlling bleeding, or giving life-saving compressions. By recognizing problems early, responding quickly, and supporting one another, surgical teams can turn a critical moment into a chance for recovery. Understanding how CPR works in the operating theatre reminds us that preparation, coordination, and clear communication are the real keys to protecting lives when time is short.